Breadcrumb

The Lunchtime Portraits: a Christ Church librarian’s 10-year portrait of Oxford

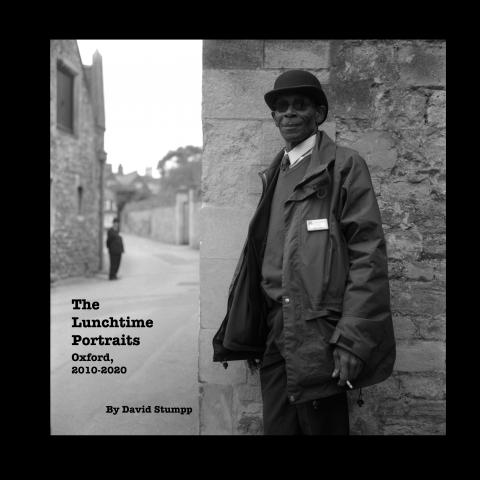

Alongside his work as Rare Books Librarian at Christ Church, David Stumpp is a committed photographer – so much so that his newly published collection of photographs is the culmination of a decade’s work. The Lunchtime Portraits: Oxford, 2010–2020 offers a 10-year portrait of Oxford through 180 individual photographs of the daily life with which the city teems.

Ahead of the launch of his book on 20 November, we caught up with David to uncover the story behind this long-term creative project.

In 2009, I immigrated here from Southern California. My time working on the English Short Title Catalogue at the University of California, Riverside had provided me a thorough education in early printed books, opportunities to travel to and from the United Kingdom, and, ultimately, the chance to meet and work with my wife, also a rare books librarian, who eventually landed here in Oxford. And this is where we settled, because there were few better locations in the country to use such an expertise. I started working at Christ Church in 2010 as a cataloguer for the Early Printed Books Project. I have been Rare Books Librarian here since 2022, and I am a photographer in the many spaces in between.

It’s difficult to talk about specific inspiration without mentioning my entire approach to photography. While I do have occasional projects that come to mind, and sometimes I carry them through to an end, I generally don’t tend to work from a premeditated stimulus. I rather think of photographs as having an existence all of their own, independent of any photographer with a primed camera.

What ultimately came out of this project was that it has made me fearless about photography and dealing with people.

What ultimately came out of this project was that it has made me fearless about photography and dealing with people.

When I first started working in Oxford, I took my lunches outdoors, walking the streets, seeing the city, learning my surroundings, and it occurred to me that I frequently observed, from a low-lying, subconscious level of my attention, photograph after photograph, flashing into being and then dissipating. This happened so often that I began to feel irresponsible even being aware of these events without also being proactive in some way to preserve them so they could be shared with others. From that point on, I was resolved never to be without a camera – and, also, to pay more attention.

Being naturally introverted, my camera could readily be considered a personal barrier in most social situations. Because I dislike being hemmed in by dense crowds of people, taking pictures of strangers out in the centre of a town packed with tourists was therefore a real stretch for me but a useful one. What ultimately came out of this project was that it has made me fearless about photography and dealing with people, whether it’s placating a subject who doesn’t want to be photographed or making a new acquaintance over a chat about photography or my camera.

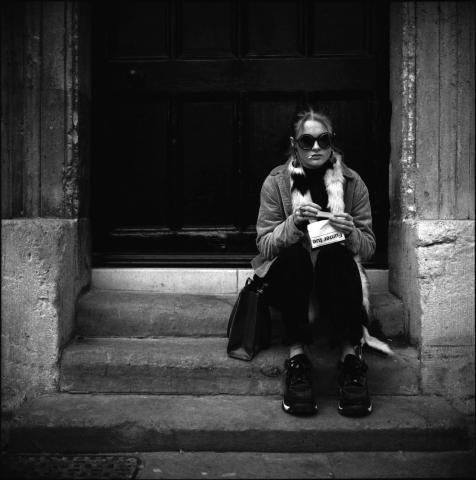

I won’t pose people. I will talk to someone first and ask whether they mind being photographed if I suspect that a conversation will further my plans, but the photographs that I take are not so much of the people themselves as they are of the moment in which those people are involved. Environmental portraits, but more. I am taking portraits of humanity, in action, en route, in the process, etc. (and sometimes of the animal kingdom, although even in those photographs, I have noticed some element of humanity).

But for some of the early days, I have photographed almost entirely in black and white, partly because I can do the whole process at home, partly because I can better afford it, but mostly because, aesthetically, I just like challenge of a black and white image. With no colour to distract or take any credit for creative impetus, the black and white image forces the brain to use other tools to process and evaluate, to think more critically, and hopefully allows the viewer to better see what I saw, what made me stop and pull out my camera in the first place.

My next book is already photographed and in the planning stages. I spent the better part of the last decade and a bit of this one documenting Oxford on the first Monday and Tuesday of every September, namely the St Giles Fair, a 400-year-old fun fair that takes place annually in an even more ancient university town. When I first thought to photograph this fascinating event, I was well aware of it already being a regular draw to photographers, but that the resulting photographs were most often night-time, long-exposure shots. Photography that quite rightly made the most of the bright, colourful lights bathing the engineering marvels of carnival monstrosities, hunched along the edges of an otherwise dark and dignified street. Being a photographer of people, though, I wanted, instead, to document the attendees and the workers against this contradictory backdrop, removing the colour and shifting the attention-grabbing illumination to the background, giving humanity the spotlight, and not even just at night, at the heart of its pandemonium but from morning setup and throughout the day. I will soon be presenting the project and these photographs to publishers.

David Stumpp will host a book launch event for The Lunchtime Portraits in Christ Church’s historic Upper Library on 20 November. Learn more and book your free place here.

Other Christ Church news