This section of highlights shows some of the items from the Jon A. Lindseth Lewis Carroll Collection, recently donated to Christ Church. Many are on display in ‘Pictures and Conversations: the Jon A. Lindseth Lewis Carroll Collection’ which runs until 17 April 2025.

The highlights include manuscripts, rare editions and photographs exploring Carroll’s life and work and enduring impact and legacy.

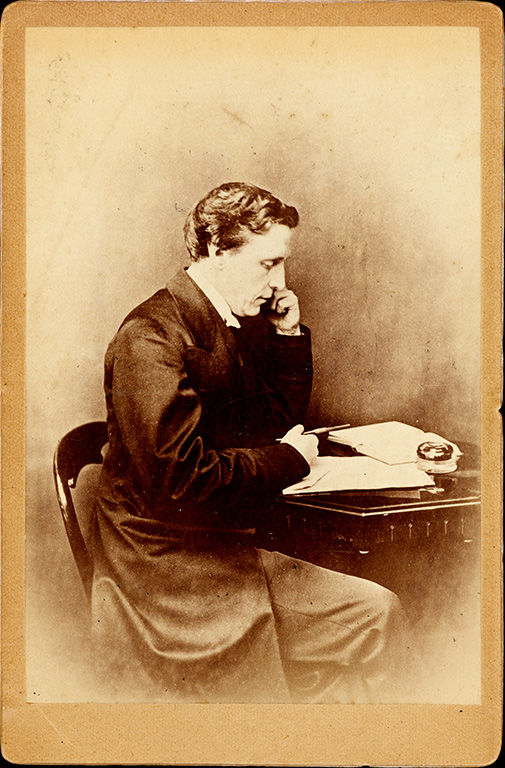

Self-portrait of Lewis Carroll

The Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832-1898) - better known as Lewis Carroll – taught mathematics at Christ Church from 1855 to 1881 before devoting himself primarily to his writing. In 1856, Carroll became friends with Henry Liddell, the new Dean of Christ Church, and his family.

His friendship with the Liddell children led him to create one of the most famous and enduring children’s stories, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Xie Kitchin dressed as a Dane

Alexandra ‘Xie’ Kitchin (1864-1925) was a child-friend and a favourite photographic subject of Carroll. She was the daughter of the Reverend George William Kitchin (1827–1912), who was Carroll's colleague at Christ Church, Oxford, and later became Dean of Winchester and then of Durham, and his wife, Alice Maud Taylor. Carroll photographed Xie around fifty times, from age four until just before her sixteenth birthday.

Carroll is considered one of the best amateur photographers of his time, particularly for his images of children. He also photographed friends, family, fellow scholars, and noted figures of his day.

Xie Kitchin — The Silhouette

Xie Kitchin — As a captive princess, 1875

Xie Kitchin — As a Chinese tea-merchant, 1873

Photograph of Edith Rix, 1885

Carroll tutored Edith Rix in logic. They became good friends and he was later reported to have said that she was the cleverest woman he ever knew. Rix, 19 at the time she met Carroll, went on to study mathematics at Cambridge and to work as a “lady computer” at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. She was one of the first women to be employed at the Royal Observatory in a professional capacity.

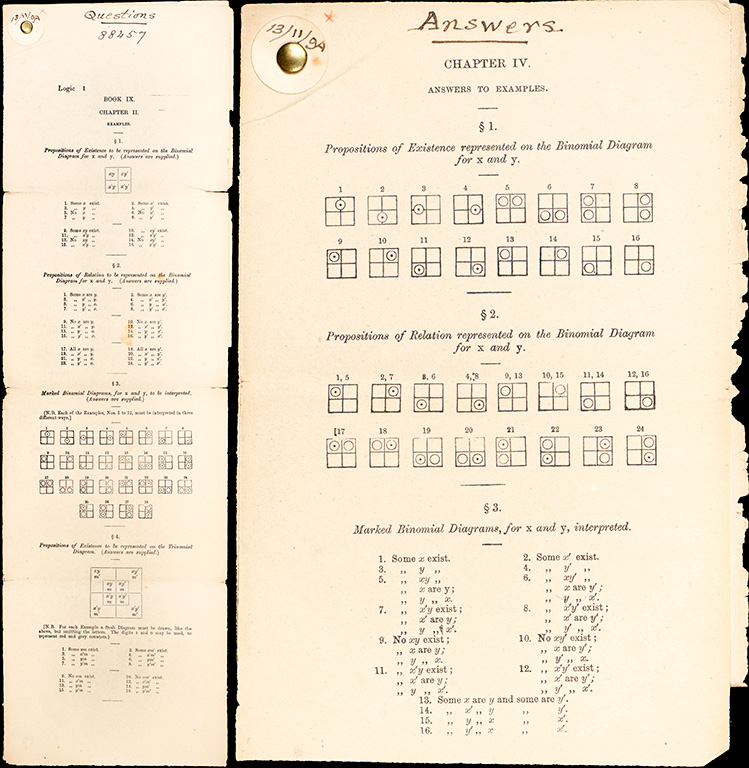

Galley Proofs for Symbolic Logic, 1894

Carroll was a respected mathematician and logician and was known for an ability to explain difficult mathematical concepts in terms that were easy to understand. He developed logic puzzles for the amusement of his siblings (even as adults) and his many child pen friends. Carroll advertised Symbolic Logic (first published in 1896) as “a fascinating mental recreation for the young”.

Carroll sent these galley proofs to May Barber, whom he had met when he taught at her mother’s boarding school in 1894.

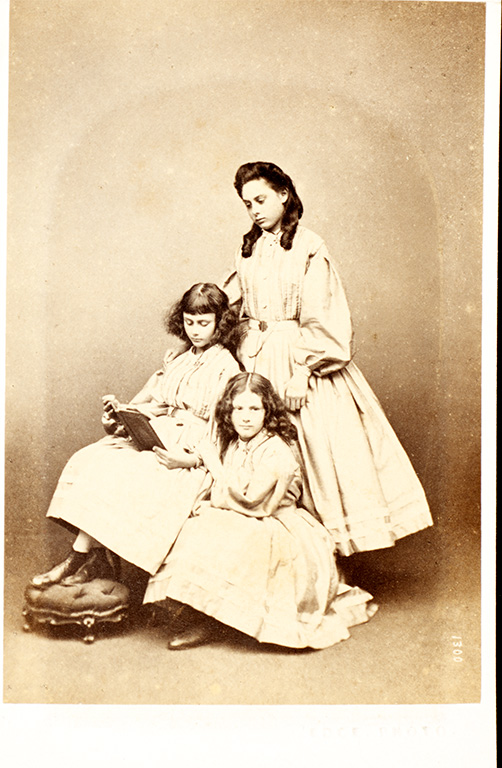

Alice, Lorina and Edith Liddell

Alice Liddell (shown reading a book) with her sisters Edith and Lorina, photographed by Thomas Edge in the mid-1860s. Alice Pleasance Liddell (1852-1934) was the inspiration for Carroll’s Alice books.

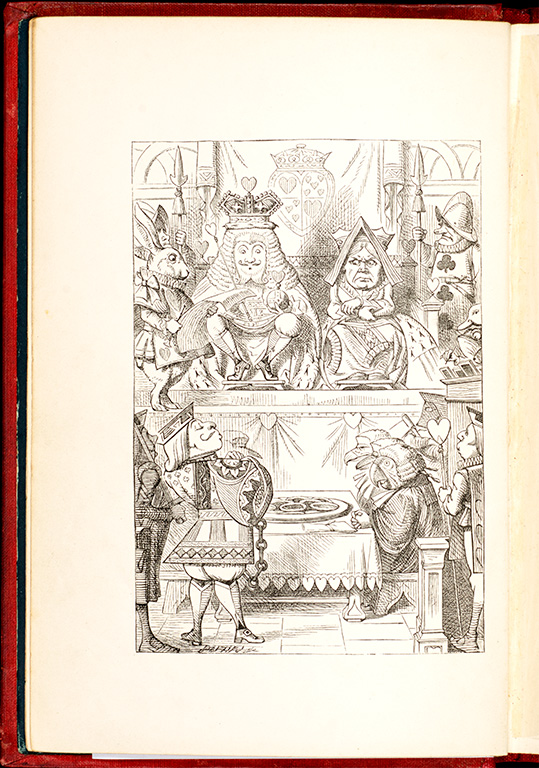

Frontispiece to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1866

The 1866 edition is the unofficial second edition, but the official first edition of the book, as the 1865 edition was recalled as Tenniel was unhappy with the quality. It was set by Richard Clay and published by Macmillan & Co. in time for the 1865 Christmas market.

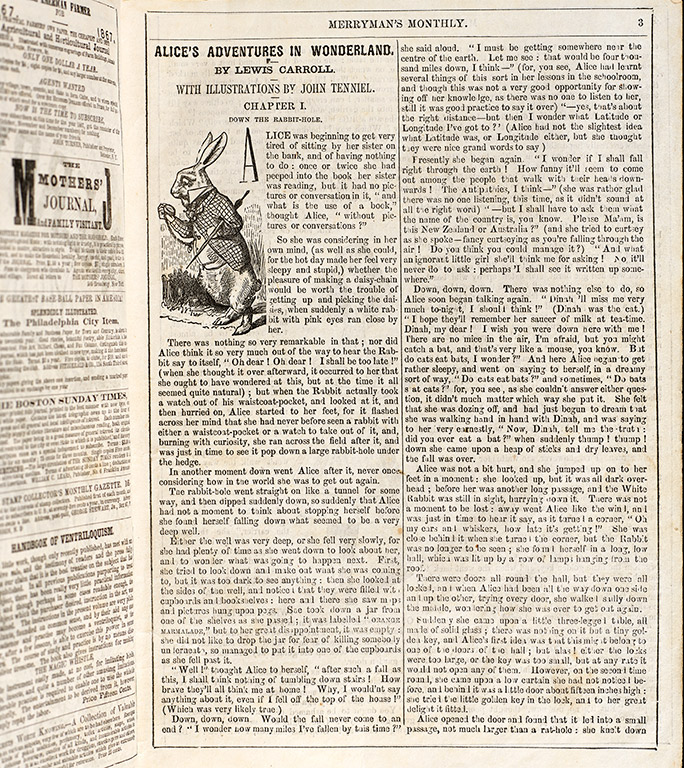

Fun For All! A Collection of Mirthful Morsels for Merry Moments (New York, 1867)

Unique copy of the first American Alice, which appeared as a pirated edition in the journal Merryman’s Monthly for January and February 1867. It contains almost the complete text of Alice, but lacks the final five paragraphs.

American copyright law did not protect foreign authors’ works from unauthorized reproduction; many pirated editions appeared after the 1866 Appleton edition. The first authorized edition to be printed in America was published in 1869.

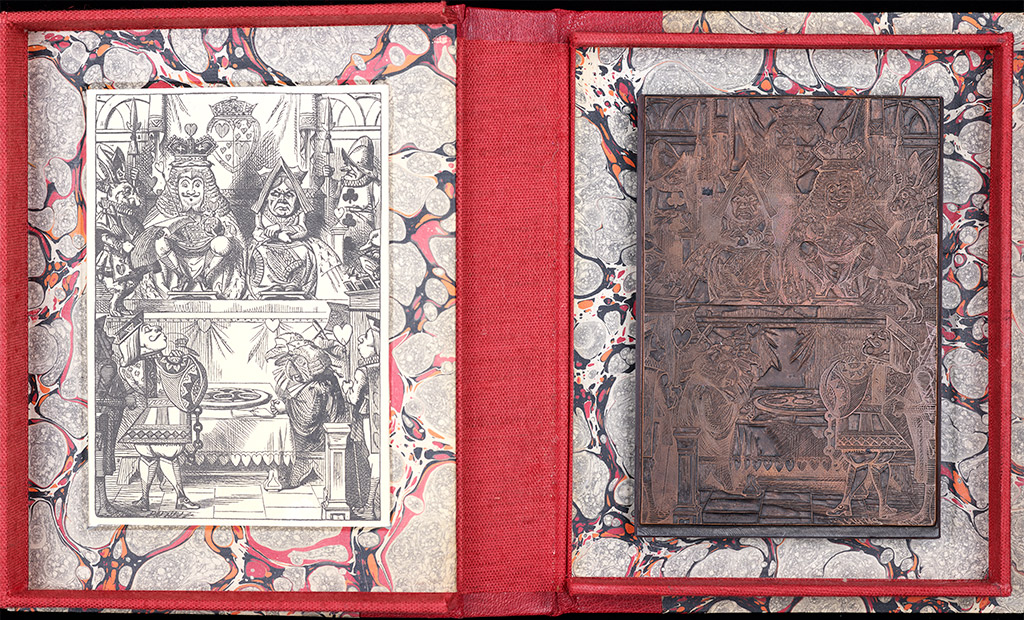

Electrotype for the frontispiece of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, People’s Edition (1887)

The Brothers Dalziel, master engravers, were commissioned to engrave the boxwood blocks on which Tenniel had made his drawings. However, the engraved blocks could not withstand commercial printing of the volume of books required, and so instead they served as the masters from which electrotype copies were made.

Carroll insisted that the illustrations for all his books be printed using electrotypes.

The songs from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (London, [1870])

The first Alice merchandise. Carroll granted William Boyd the right to compose music to the nonsense verse in Alice. Carroll was, as ever, involved in the process, and added additional lines to the poem “Tis the voice of the lobster”.

![The songs from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (London, [1870])](/sites/default/files/2025-03/13-Songs-from-Alices-Adventures-in-Wonderland.jpg)

Through the Looking-Glass (London, 1872)

The sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland appeared in late 1871, dated, as was common practice for Christmas books, the following year. Though initially reluctant, John Tenniel again provided the illustrations. This copy bears an inscription from Tenniel, using his characteristic monogram, and a pencil reproduction of the illustration of Alice wearing her golden crown.

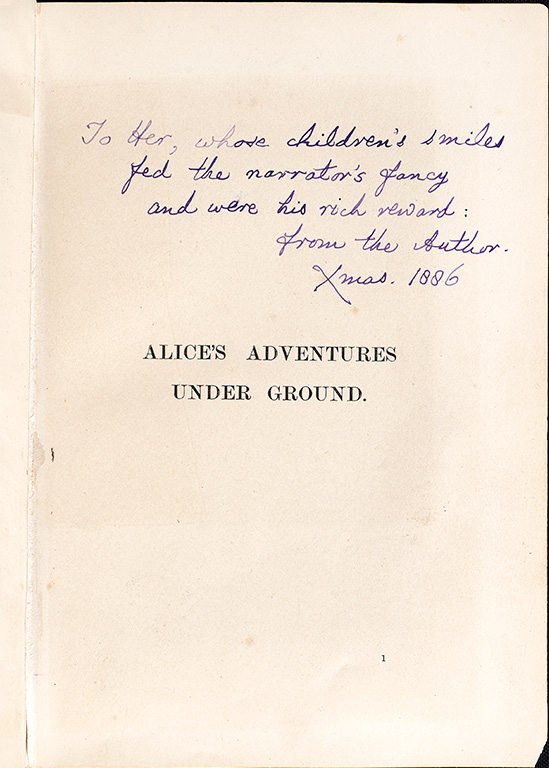

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground (London, 1886)

The original manuscript of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, the tale which became Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, was given to Alice Liddell as “a Christmas gift” in 1864. More than twenty years later, it was published in facsimile, complete with Carroll’s original illustrations. This copy is inscribed in the author’s hand to Lorina Liddell, Alice’s mother.

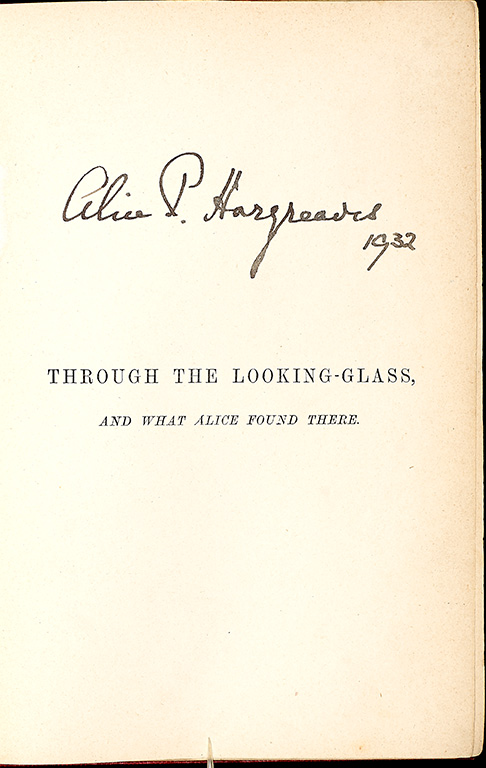

Through the Looking-Glass (New York & London, 1872)

A number of copies of early editions and translations of the Alice books survive with the signature of the original Alice in later life, by this time Alice Hargreaves, widow of Reginald and chatelaine of Cuffnells, a large house in the New Forest. Many of these signatures are dated 1932, in which year she paid a much-publicised visit to New York with her son Caryl. Alice died two years later, in 1934, at the age of 82.

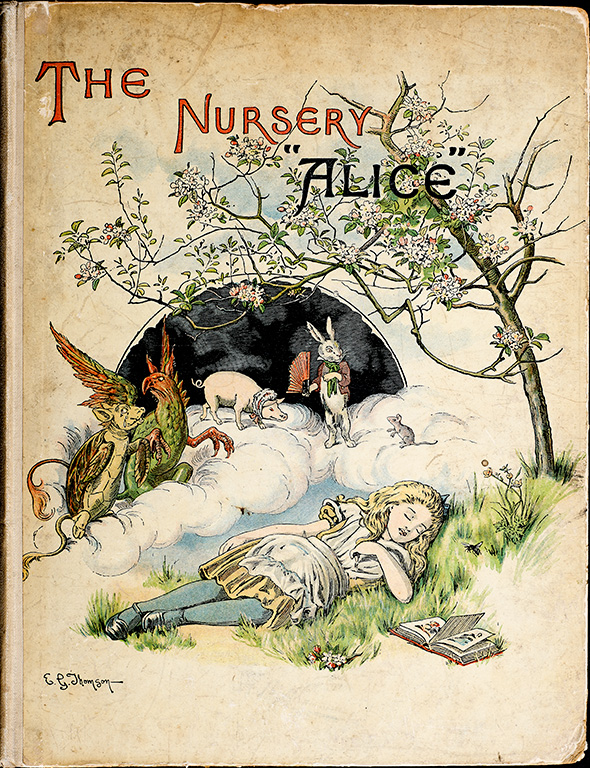

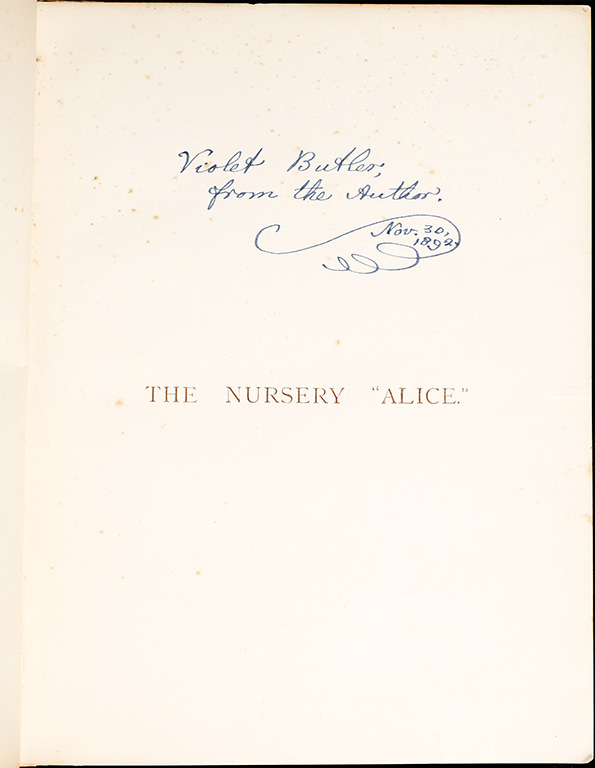

The Nursery “Alice” (London, 1890)

The last book in the Alice series tells a simplified version of the Wonderland story for very young children “aged from Nought to Five”, with enlarged and coloured versions of the original illustrations by Tenniel. This copy is inscribed to Violet Butler, then aged eight, a niece of social reformer Josephine Butler who in later life was tutor in economics at St Anne’s College and a pioneer in social work education.

The Nursery “Alice” (London, 1890)

Carroll to Ruth Butler. Autograph letter, 24 November 1892

On 3 November 1892, Carroll met Arthur Butler and his eldest daughter, Olive, riding in Oxford. Carroll had been at Rugby School with Butler, who went on to be headmaster of Haileybury College and a fellow of Oriel College. After this re-acquaintance, Carroll started to correspond regularly with Arthur and his three daughters Olive, Ruth and Violet.

In this letter, Carroll jokes with Ruth about his inquisitiveness before asking which of his books the family possesses. Carroll sent Sylvie and Bruno to Olive, Alice’s Adventures Underground to Ruth and The Nursery Alice to Violet.

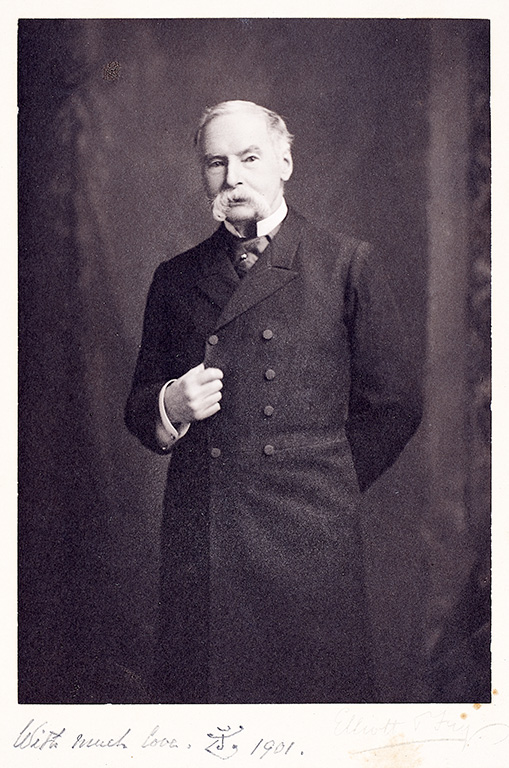

Sir John Tenniel, 1901

Lewis Carroll originally illustrated Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland himself, but approached John Tenniel whose work he had admired in Punch, to illustrate the edition that Macmillan agreed to publish in 1865. Each illustration was drawn on boxwood; the illustration was then sent to the engravers who engraved the block for printing.

For many of the illustrations, Tenniel (1820-1914) was given precise instructions from Carroll, but this infuriated the artist who almost turned down the request to illustrate Through the Looking-Glass because of Carroll’s constant interference. Carroll and Tenniel even argued about the look of Alice herself.

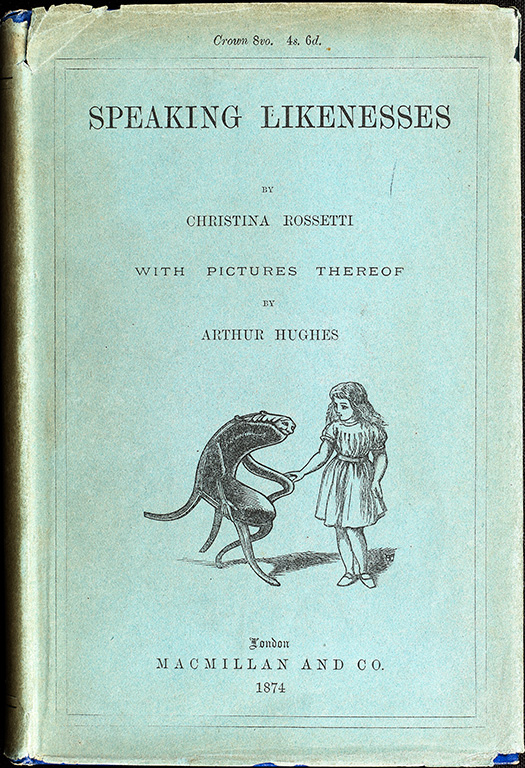

Christina Rossetti, Speaking Likenesses (London, 1874)

First edition of the first Alice parody. Described as ‘angry subversion of Alice’s adventures’, Speaking Likenesses was a collaboration between Christina Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite artist Arthur Hughes, with illustrations often derived from original sketches by Rossetti herself. The book was produced for the children's Christmas market and drew considerable inspiration from Lewis Carroll's Alice books, a debt readily acknowledged by Christina Rossetti who knew Carroll personally.

In its anonymous review of the book, the Academy noted rather hopelessly: “This will probably be one of the most popular children's books this winter. We wish we could understand it”.

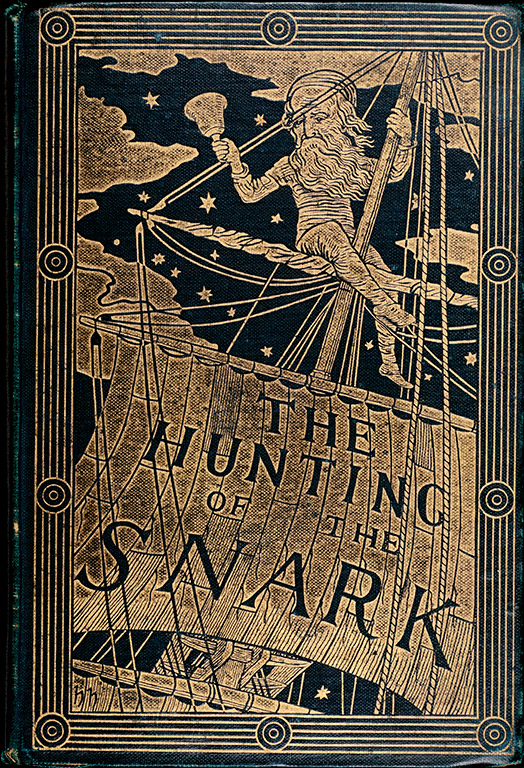

The Hunting of the Snark (London, 1876)

Probably Carroll’s best-known work after the Alice books, the narrative poem The Hunting of the Snark grew from its final line “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see”, which occurred to the author on a morning walk after a restless night. The illustrations were by Henry Holiday, otherwise remembered chiefly for his work in stained glass.

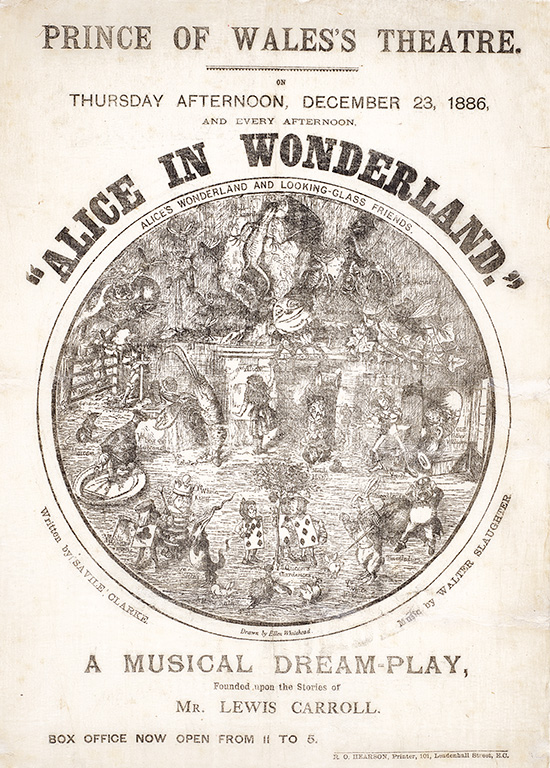

Poster for Alice in Wonderland, "A Musical Dream Play”, 1886

In 1886, Carroll was approached by aspiring playwright Henry Savile Clarke, who wished to stage Alice as a two-act operetta. Carroll agreed, on the condition that no coarseness be allowed. He insisted on working closely with Savile Clarke, contributing additional verse to the production and making numerous suggestions for child actors to play various roles.

The first performance was on 23 December 1886 at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre, London, Carroll's twelve-year-old friend Phoebe Carlo in the lead role of Alice. This first production was very successful. A revival in 1888 at the Globe Theatre with Isa Bowman as Alice was not a financial success, and the operetta was not performed again until after Carroll’s death.

Phoebe Carlo as Alice, 23 Dec 1886

Carroll selected Pheobe Carlo for the role of Alice in Alice in Wonderland, "A Musical Dream Play”.

The Theatre wrote this review in 1886: “Alice in Wonderland will not appeal to the children alone. ... Mr. Savile Clark has done wonders. ... The play is beautifully mounted, and splendidly acted, Miss Phœbe Carlo being very successful as the little heroine... she played in a delightful and thoroughly artistic fashion.”

Lewis Carroll, Ania v stranie chudes [in Cyrillic]. Translated by V. Sirin [pseudonym of Vladimir Nabokov] (Berlin, 1923)

Alice was first published in Russian by an unknown translator in 1879. Vladimir Nabokov (1900-1945) first read Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in English at age six. He began its most famous Russian translation 18 years later while an undergraduate at Cambridge University. This was his first substantial published work, for which he was paid the equivalent of the then-considerable sum of five dollars.

To make the story relevant for a Russian audience, Nabokov retold it in a Russian style and gave Alice a new name: “Ania”. Like all of Nabokov’s writings, his translation of Alice was banned in the USSR and was not published there until 1989. This edition, the first, had already become a rarity.

With illustrations by S.V. Zalshupin (1898-1931) in the Russian Constructivist style.

![Lewis Carroll, Ania v stranie chudes [in Cyrillic]. Translated by V. Sirin [pseudonym of Vladimir Nabokov] (Berlin, 1923)](/sites/default/files/2025-03/25-Alices-Adventures-in-Wonderland-translated-into-Russian-by-Valdimir-Nabokov-Berlin-1923.jpg)