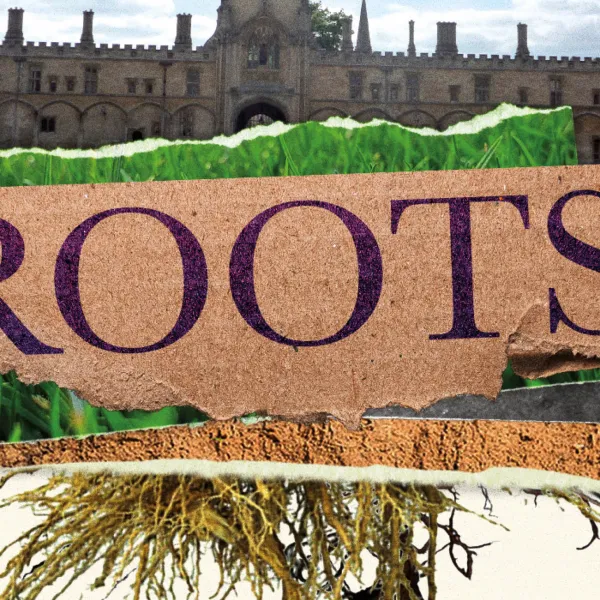

The 25th Christopher Tower Poetry Competition is now closed, as of midday, 20th February 2025. Students between 16-18 years of age were challenged to write a poem on the theme of 'Roots'.

All entrants have now been informed of the outcome. Please check your Submittable account if you have not received an email.

About the Competition

The Tower Poetry Competition offers the UK’s most valuable prize for young poets. The competition is free to enter and it is open to students between 16-18 years of age who are educated in the UK.

The competition is judged anonymously by two guest judges, who are different each year, and the Christopher Tower Student. Each year the theme is chosen with the intention of giving entrants free rein to interpret it as widely as they like.

The poet who writes the best single poem on the theme receives £5000. There will be a second prize of £3000, and a third prize of £1500. Along with these, there will be ten runners up, who will each receive £500. The top three winners will also be offered a future place on the Tower Poetry Summer School.

The 2025 competition is now closed.

Where do I start?

Looking for some inspiration? The Christopher Tower Poetry Competition has been running for over two decades, and in that time has rewarded over 120 young winners and their poems. Take a look at entries by past winners on the 'Previous Competitions' page.

Remember to also read through the competition Terms and Conditions and the Frequently Asked Questions, both below.

Terms and Conditions:

- Entrants must be at least 16 years of age, and under 19 years of age, on 20 February 2025.

- Entrants must be in full or part-time secondary education in the United Kingdom. Students enrolled on higher education courses are not eligible to enter the competition.

- Entries for the Tower Poetry Prize 2025 must be on the designated theme.

- Entries must be written in English, and be no more than 48 lines in length.

- Entry must be made via the website, with true and accurate information given.

- The closing date for entries is 12 noon on 20 February 2025. Entries entered after noon will not be considered by the judges.

- Each entrant may submit only one poem.

- Poems may not be edited after they are submitted to the Tower Poetry Competition; only the first entry will be considered.

- Poems with joint authorship are ineligible.

- Each poem must be the entrant’s own work: it must not incorporate poetry by others without acknowledgement and (where appropriate) citation, and it must not include substantial elements (phrases, lines, or larger blocks of composition) that have been suggested or authored by others engaged in providing specific editorial advice to the entrant.

- Entries must not have been created using AI.

- Poems must not have been previously published, broadcast or submitted to another competition.

- Names and addresses must not be included with the text of the poem, since entries are judged anonymously.

- 'Track changes' must be removed before submitting the poem.

- The judges’ decision is final, and no correspondence will be entered into concerning this decision.

- The copyright of each poem remains with the author. Authors of the winning poems will grant Christ Church permission to publish or broadcast the poems for a period of one year from 23 April 2025. The competition is not open to family members or close relatives of employees of Christ Church, Oxford.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Do I need to be a poet to enter?

Peter McDonald:

What is “a poet” anyway? I’m certainly not sure that I know an answer to that. Very few people aged between 16 and 18 are “poets” in the sense of writing poetry continually, and taking what they write seriously in order to write more of it – very few people of any age are, in fact. It doesn’t matter who you are – where you’re from, what you do, what you like to listen to, watch, or have for breakfast – there’s plenty in you that can help to write a real poem.

What we’re looking for are poems, and poems that work: you might never have written one before, and might never write another one again, but that doesn’t stop you from writing a poem now that will bowl the judges over. No entry is ever judged on how well it approximates to somebody’s idea of what the work of “a poet” should look like: think of an entry as a single piece of verbal arrangement, with a job to do and lots of resources – in the language, and in you – to draw upon.

-

Why have a set competition theme?

Peter McDonald:

At Tower Poetry, we certainly believe that thinking your way into a theme is a creative act, and one which helps, rather than hinders, the kinds of creativity that go into writing a proper poem. It also means that everyone entering comes in on broadly the same terms. Remember that a theme is not a narrow thing, and ours are designed to give you lots of scope for your own intellectual engagement. This isn’t to say that you should set out to do something really unexpected and unusual with a theme – an approach which is fine if it comes naturally, and chimes with the ways in which your poem works, but almost never successful if it’s just a policy decision taken in advance, with the poem having to follow instructions. The difference always shows.

-

How should I approach the competition theme?

Peter McDonald:

If the poem’s a good one, the theme will be clear, even – perhaps especially – if that relation is quite subtle. Don’t try to pass off a piece that really has no relation to the theme as some kind of super-subtle approach to it. Equally, don’t put the judges to school by making your point stridently and repeatedly in the poem. You don’t have to spell everything out: just think hard before you start writing. It's fair to say, though, that the most obvious approach can sometimes be the trickiest to pull off, and it’s worth thinking for a while about various possibilities that the theme might open for you.

-

Why are entries limited to 48 lines?

Peter McDonald:

We want to see what you can do within the limit of (at most) a substantially-sized lyric poem. 48 lines offers flexibility – six eight-line stanzas, for example, or eight six-line ones; twelve quatrains, perhaps, or 16 versets of terza rima (should you be so inclined). However, our limit does not mean that your poem should be 48 lines long, and will be penalized for failing to reach that length - our judges don’t take 48 as a magic number, or think any less of a 47-line piece. Look through past winners, and you will see that much shorter poems have often done very well.

-

Are there expectations about poetic form?

Peter McDonald:

None at all. The judges don’t give extra points for something just because it’s cast in a certain form unless that form really adds something, and is intrinsically a part of what the poem is saying. But don’t think that there’s an easy alternative to “form”: in a way, every real poem has a form of its own, whether it rhymes or not, whether it’s in stanzas or not, and whether or not its rhythms and line-lengths are in any kind of pattern. Good free verse is just as demanding as something formally intricate, and leaves your style just as exposed. Think of form not as a hurdle standing in your way, but as an essential and enabling tool.

When learning how to write, your best helper is your own reading. Look again at things you like; take them to pieces, and see how they work. Why that rhyme? Why that line-length, and here rather than there? Why that kind of ending? Why the strange expression rather than the obvious one? Do this for long enough, and you will be equipping yourself with the kinds of composing reflexes your poem will benefit from.

-

Is there anything I should avoid?

Peter McDonald:

Try not to use clichés, look out for bad grammar, avoid too-obvious or clunky rhymes, and steer well clear of archaic English ('thou', 'thee’, 'thine' etc. may make your poem sound like something written 200 years ago, but remember, good imitation is very difficult indeed; anything else can look clumsy, or worse). Try not to go too far in the other direction, either: stream-of-consciousness, like direct transcription of casual talk, is terribly hard to turn into good poetry.

Above all, please remember that the poem is judged on how well it does the thing it sets out to do, rather than on the merits of what is claims to be 'about': that means that style – careful writing, a sense of phrases and their rhythms, a feeling for sentences, a grasp of words as both simple and complicated things – is at a premium.